When the topic of domains and email comes up most people begin and end the conversation at the top domain level. Subdomains seem to be left out of the conversation in their entirety. Are we trapped in our thinking about subdomains as mere marketing and newsletter features? Maybe it’s too difficult to use subdomains without an IT team involved. Maybe no one has brought up subdomains outside of meme-filled newsletters. Maybe you just haven’t thought about subdomains in general.

Well, let’s break up that thinking. Subdomains have a lot to offer. Do you have trouble testing 10 different email features in your application? Does the thought of accidentally sending an email to thousands of users that says “Test” make you break into a cold sweat? Subdomains can help.

We’ll show you some of the possibilities of subdomains and walk through some use cases. We’ll also provide a quick 15-second walkthrough at the end that will setup up 2 new subdomains for development and testing purposes.

And we’ll do all this using Mailsac’s Zero-Config subdomain feature.

But before we show you some of the juicy scenarios, let’s do a quick rundown of what a subdomain actually is.

What’s the difference between an email domain and a subdomain?

Subdomains are a way to slice up domains for specific functions like newsletters and blogs. The advantage of a subdomain is having a clear purpose tied to the name. Receiving emails from tom@memenews.mailsac.com and jane@hottakes.mailsac.com show their intent from their name alone. Receiving emails from tom@mailsac.com and jane@mailsac.com is a lot vaguer. The former set clearly sends memes and educational nuggets. The latter could be a friendly name for our billing bots.

Subdomains = an easy way to differentiate email by function.

Alright, sorry about that. Had to make sure everyone was on the same page on subdomains. Let’s move on to 3 different subdomain scenarios.

Subdomain Use Case 1: Developers Get Their Own Email Domains

You work on a team of developers, and each of you needs to test the same features on a few different applications. Additionally, each feature has an email workflow attached to it. The usual response to this is to have a shared inbox, for example, timesheetsystem-dev@acme.com. But the pain around that approach comes fast. Issues like:

- Difficulty in separating out each developer’s testing scenarios

- Having to sift through 1000 other unrelated emails while looking for that 1 workflow email is painful

- Complex workflows are pretty difficult to track

Creating an email subdomain per developer is an effective way to isolate these emails across systems:

- Jon gets:

- timesheets@acme-jon.msdc.co

- billing@acme-jon.msdc.co

- travel@acme-jon.mdsc.co

- Emma gets:

- timesheets@acme-emma.msdc.co

- billing@acme-emma.msdc.co

- travel@acme-emma.msdc.co

Remember that you don’t need to create these inboxes ahead of time. They are made on the fly and removed when they make sense for you, the person knee-deep in the application.

Also not shown above just yet: Mailsac’s unified inbox in action.

Subdomain Use Case 2: Company-Wide Domains per Environment

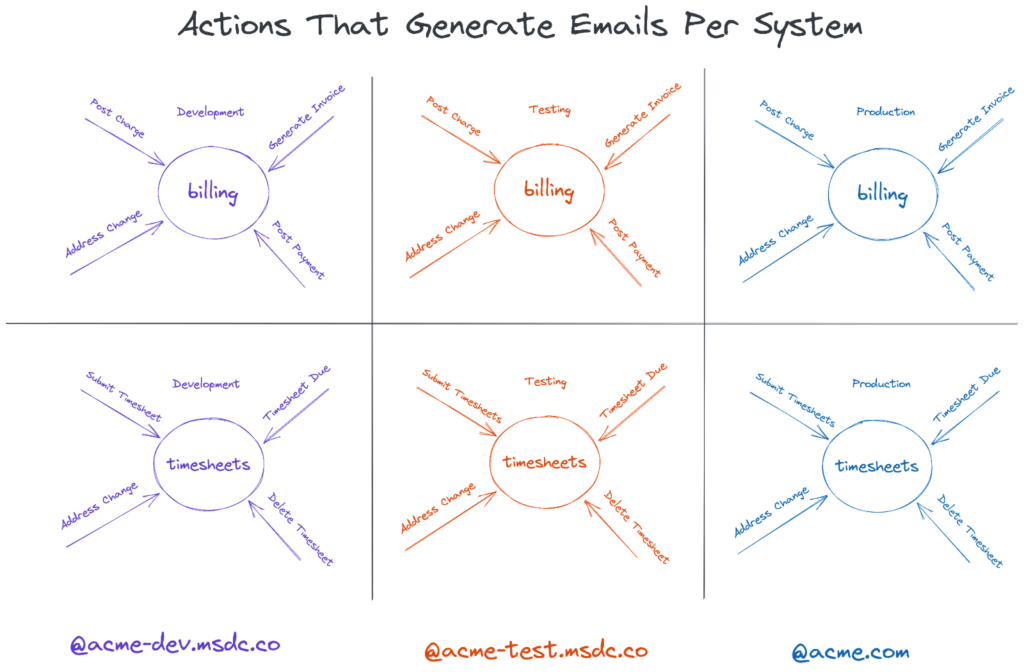

Environments for each set of applications are a pretty common scenario amongst enterprises. A sample above shows 2 applications split between 3 environments:

- timesheets@acme-dev.msdc.co

- timesheets@acme-test.msdc.co

- timesheets@acme.com

- billing@acme-dev.msdc.co

- billing@acme-test.msdc.co

- billing@acme.com

The upside of this approach is having predefined email subdomains for each environment. Developers, QA teams, and operations all know which environment the emails are associated with. QA testers can review the messages easily knowing which environment sent the emails. Operations and developers know which email address and domain to use as variables when configuring tests or environments. Ultimately, this saves time for all the teams involved.

Subdomain Use Case 3: Email Driven API Workflow

An email-driven API workflow is a workflow that kicks off when an email arrives. The approach resembles the first scenario, where each developer gets their own domain. The difference is the usernames are less flexible. You pin it once to an API and use it for the long term. For example:

- An email to submit@acme-emma.msdc.co can trigger a Submit API action that can create a case in the HR management system

- An email to hr-help@acme-emma.msdc.co can trigger an Integration API action that can automatically create a ticketing workflow in your Incident Management system.

You can even string together a received email to a webhook using Mailsac’s webhook service. If you’d like to poll for updates instead we have websocket for close to real-time processing or the rest API for polling.

Alright, enough theory let’s do a walkthrough.

Walkthrough: Company-Wide Environments

Using the company-wide scenario we can have a working subdomain in a few seconds using Mailsac. A partner video will walk through the individual developer scenario.

You also have the option of using your own domain. This requires an external domain service provider. There are lots of guides out there on which domain registrar is the best.

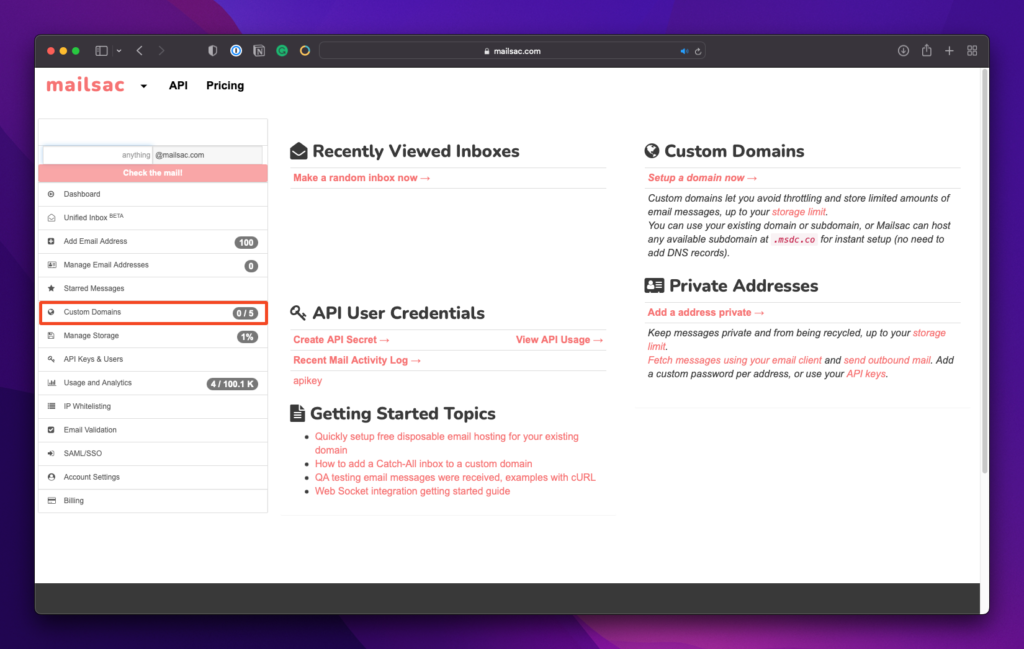

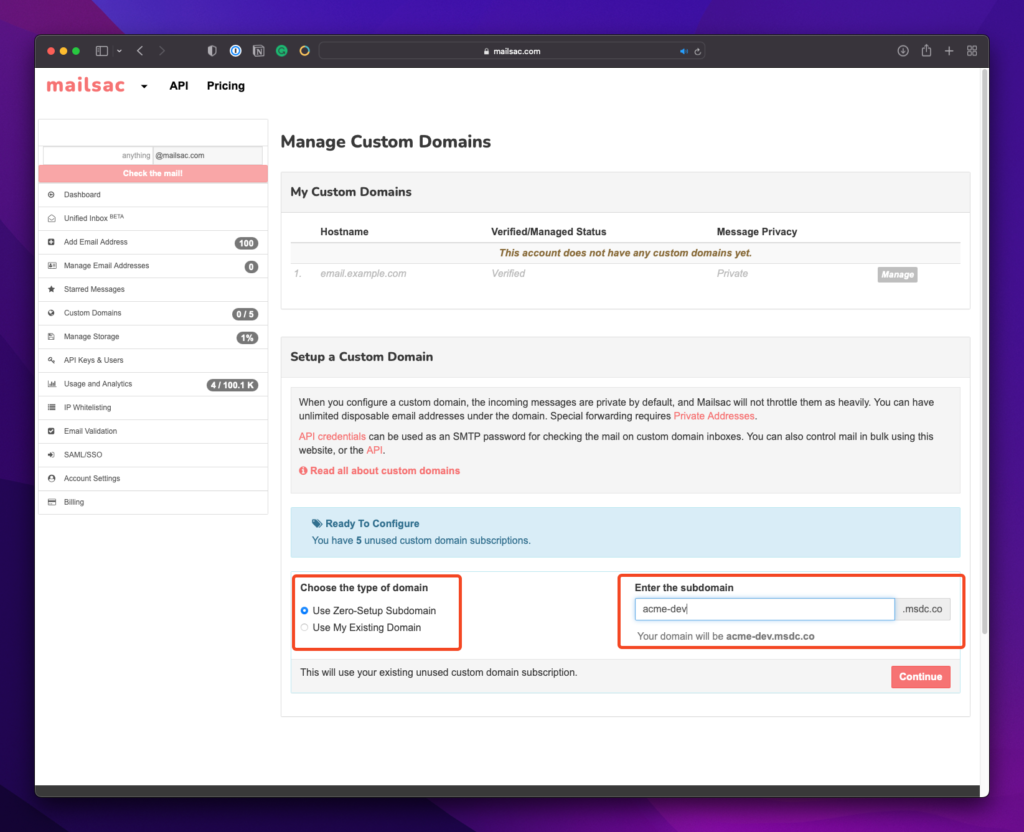

But let’s make this easy. Let’s use Mailsac’s Zero-Config Subdomain tool and bring up a new subdomain in 2 clicks. Note that you will need at least a Business Plan to make this scenario work. You can still enjoy the benefits of a single subdomain through the Indie Plan.

Zero-Click Subdomain

After creating a Mailsac account, navigate to “Custom Domains” from your dashboard:

Type the name of the subdomain you’d like, in our case acme-dev and acme-test

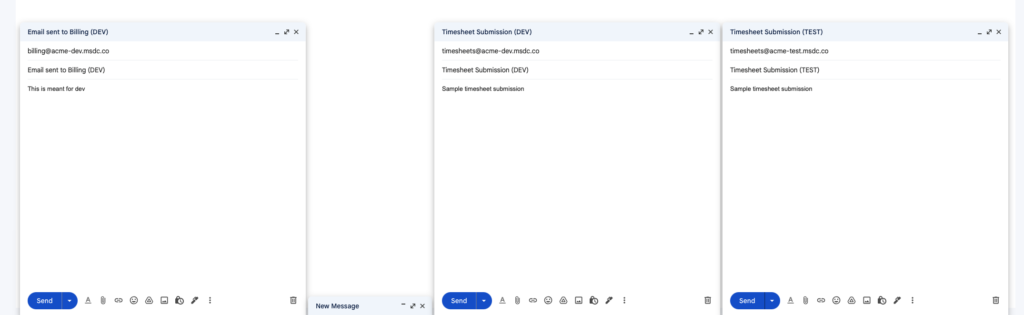

And that’s it! You should have 2 custom subdomains ready to use. Let’s put it them rough their paces. We’ll send out these emails from any client (I’ll use Gmail):

- To: billing@acme-dev.msdc.co

Subject: Email sent to Billing (DEV)

Content: This is meant for dev - To: timesheets@acme-dev.msdc.co

Subject: Timesheet Submission (DEV)

Content: Sample timesheet submission - To: timesheets@acme-test.msdc.co

Subject: Timesheet Submission (TEST)

Content: Sample timesheet submission

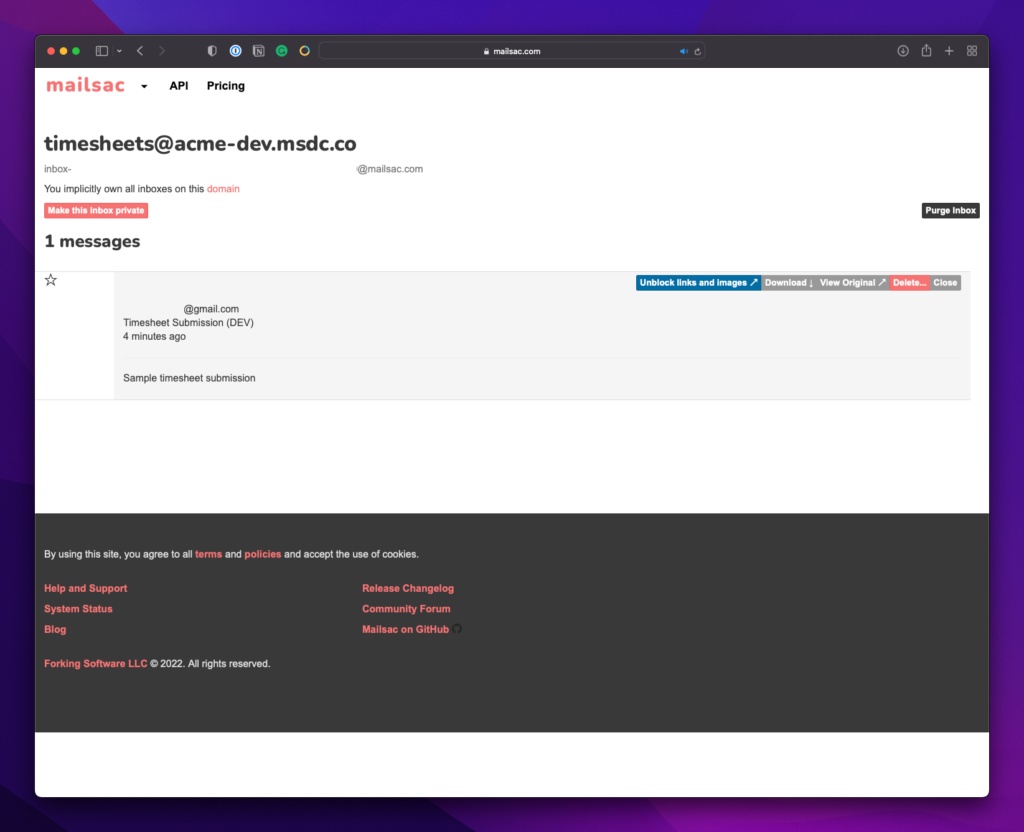

After submitting your set of emails, you *could* just check timesheets@acme-dev.msdc.co and timesheets@acme-test.msdc.co individually…

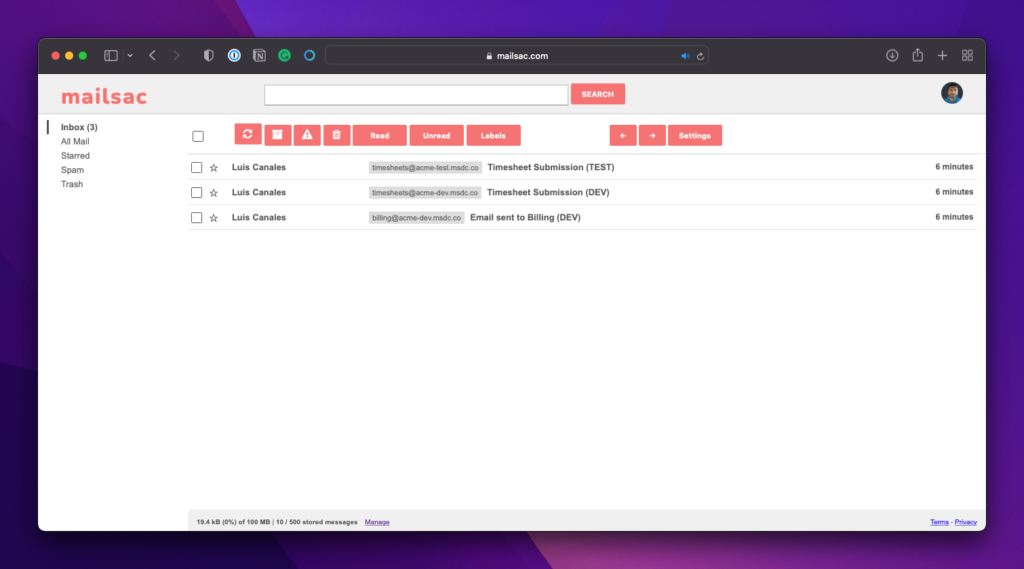

…or you could use the Unified Inbox feature that displays all of your custom domains, subdomains, and private addresses in one convenient location:

It’s just that easy!

Wrap Up

With this new superpower, you should be able to conjure up lots of different use cases for subdomains. The friction of creating and importing domains is completely taken care of for you. No need to register a domain with an external registrar, or manage an IT team to handle registration for you.

We’re always looking for feedback, so let us know what you think or if you run into any problems on our forums.